My paternal grandmother, Charlotte, had a repertoire of stories that she would often tell and re-tell at family gatherings. Some of these were about the memories she had of her children and grandchildren, even of her own childhood – and the stories were always told, word-for-word, in exactly the same way. Each family member could recite them by rote.

Ancestry

Adventures in Ancestry: The Acadian Connection

On a mid-summer day in 1755, Jean-Baptiste Guillot, my 7th great-grandfather, looked around him, at the land he farmed and the home he built. He was a proud and content Acadian, living in Ile Saint-Jean, a small Canadian maritime community.

This was the only life he had ever known, since he had been born in Cobequid on nearby Acadia, a French colony first settled in the early 1600s by people eager to escape the religious wars of Europe and the hardships of feudal life and the poverty they brought. Jean-Baptiste still had a difficult time calling it Nova Scotia, the name the English gave to it when they gained control in 1713, as part of the Treaty of Utrecht.

Adventures in Ancestry: A Revolutionary Tale

Only 15 miles separated Weymouth, MA, from Boston, but very often it felt as if the small village was a world away. Where Boston was a large and bustling seaport, the jewel of the Massachusetts colony, Weymouth, officially founded in 1622, remained rural and agricultural. Residents held fast to the traditions of New England, including town meetings and strong community ties.

Adventures In Ancestry: The Mystery of Crocifissa, Parte Seconda

After solving the mystery of how my great-grandparents, Giuseppe and Crocifissa, had met and married in Independence, LA, I was energized to learn more. I already had proof of Giuseppe’s arrival in the United States, but I knew nothing of Crocifissa’s arrival.

So much of her life remained a mystery – and I wondered how far back in time could I travel without ever leaving my house?

Adventures in Ancestry: The Mystery of Crocifissa, Parte Uno

Part of what I truly enjoy about genealogy is the detective work, finding clues and fitting the puzzle pieces together to create a more complete picture of my ancestors. Such was the case as I worked on my great-grandfather Giuseppe’s history. As the picture of his life came into focus, there was one, very large, missing detail:

Adventures in Ancestry: My Sicilian Rabbit Hole

Picture it: Sicily. 1887. In the small village of Bisacquino (pictured above, courtesy of the Southern Italy Genealogical Center), a son is born to Salvatore and Maria. They name him Giuseppe and this is the start of my great-grandfather’s story, as well as my own, as I research his life and his connection to me.

That connection, by the way, seems to have stretched through time. After we returned from Sicily in April and I started playing with ChatGPT (other than some of the photos in this piece, this post is all me), I asked the program to draw me as a Sicilian peasant.

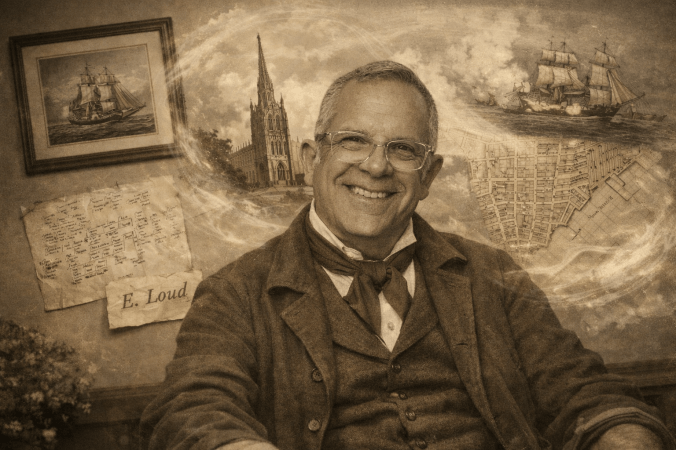

Adventures In Ancestry: Growing Up Loud

When I was very young, I never gave my surname, Loud, a second thought. That’s probably because I had never met or heard of any other Louds, other than the Louds in my small immediate family and in my small extended family. It was a small Loud world, after all.