My paternal grandmother, Charlotte, had a repertoire of stories that she would often tell and re-tell at family gatherings. Some of these were about the memories she had of her children and grandchildren, even of her own childhood – and the stories were always told, word-for-word, in exactly the same way. Each family member could recite them by rote.

One of those stories was about the Loud fortune, something she said she was told when my paternal grandfather was courting her. The Louds, it was claimed, were sitting on a fortune – one that included the land in lower Manhattan on which Trinity Church had been built.

If you’re not familiar with Trinity Church, here’s a quick summary. The original church was founded in 1697, more than 20 years after my ancestor, Francis Loud, arrived in North America. The current Gothic Revival-style building was completed in the 1840s – and the cemetery is a Who’s Who of the Deceased: Alexander Hamilton, his wife, Eliza, Robert Fulton (engineer and inventor of the steamboat), John Jacob Astor IV, and John James Audubon.

Needless to say, as we all sat around my grandparents’ dining room table in their very, very modest home in Ozone Park, Queens, NY, we, including my grandmother, all knew the truth — there had never been a Loud fortune.

Still, my questions had a way of lingering: How did this legend even start? Was it a practical joke to prank my grandmother? Was it something she made up to entertain us? Or was their some truth to it?

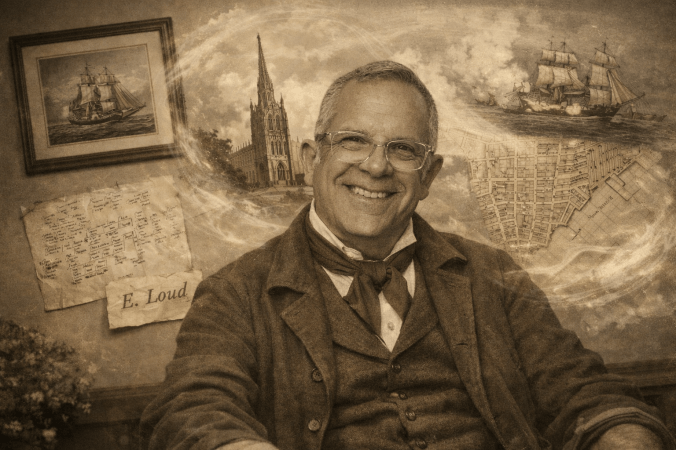

Many years later, I think I found my answers, when I met Ebenezer Loud, my 4x-great-grandfather, on page 429 of 300 Years of Louds in America.

Ebenezer Loud, with his hat commemorating the War of 1812. Courtesy of 300 Years of Louds in America. Colorized by ChatGPT.

In 1795, Ebenezer Loud entered the world. The nation was just 19 years old, and many of the men in his life, including his father and grandfather, fought in the American Revolution.

The young family grew, so much so that in 1805 Ebenezer – along with his parents, David and Sarah Loud, and his siblings, moved from South Weymouth, MA, to Braintree, a little more than four miles away. This new hometown was the birthplace of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, as well as of John Hancock.

Between his DNA and the history surrounding him, it’s fair to say that service to country was in Ebenezer’s blood – and that sense was put to the test just seven years later, when the United States was in a standoff with Great Britain over American maritime rights.

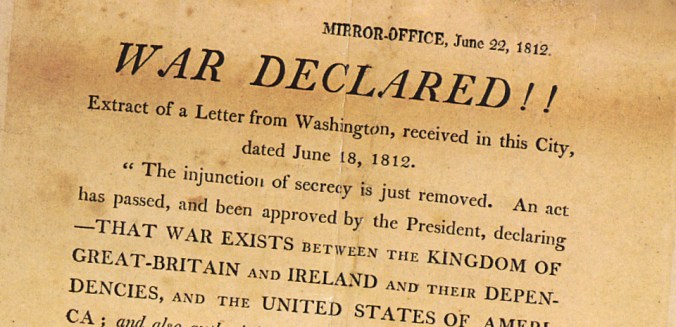

At that time, President James Madison asked a divided Congress to declare war. Democratic-Republicans from the southern states were pushing for war, while Federalists from New England saw no need for it, especially because they felt the country was unprepared. The army and navy, they believed, had been neglected under the Madison Administration, as well as that of Thomas Jefferson.

The measure passed along Party lines on June 18, 1812, and the United States was once again at war with Great Britain. The conflict, known in history books as the War of 1812, was also considered America’s “Second War of Independence.”

One month later, David Loud, Ebenezer’s father and veteran soldier of the Revolution, enlisted. In October, 17-year-old Ebenezer did the same, serving on the USS Chesapeake under Captain James Lawrence. On official documents, he’s listed as a private, but his role on the ship was that of a powder monkey, responsible for carrying gunpowder from below deck to the cannons during battle.

One British strategy was to establish a blockade of Boston Harbor. In late May 1813, the HMS Shannon, under the command of Captain Philip Bowes Vere Broke, moved into the harbor. On June 1, Captain Broke challenged Captain Lawrence to “the maritime equivalent of a duel.” Both captains agreed to have their ships meet at the Boston Light, unassisted by other ships, in the late afternoon, “in full view of Bostonians who congregated on rooftops to watch the showdown.”

Ebenezer, each fiber of every muscle in his teenage body tense, was prepared to do all that a powder monkey could do to achieve victory for his Captain and his country.

The battle began at 6:00 pm. It was over by 6:14.

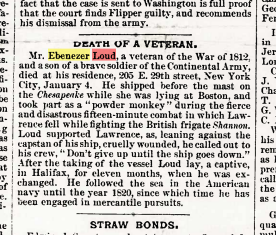

Within minutes, Captain Lawrence was hit twice, and his first lieutenant was also injured. Mortally wounded and leaning against the capstan, Lawrence was, according to Ebenezer’s 1882 obituary in The National Tribune, “supported by Loud.” From that position, he continued to issue orders to his American officers, “Don’t give up the ship,” five words that would live on in naval history. Quickly, though, officers ordered that he be brought below deck, which left no leadership on deck at a critical moment in the battle.

Damage to the Chesapeake’s sails made it nearly impossible for the crew to maneuver the frigate, which allowed a British boarding party to overwhelm the crew. It was said that Ebenezer, in his later years, would tell his children and grandchildren of the “hand-to-hand and life-for-life” combat aboard the Chesapeake.

At the end of those 14 minutes, 252 men were dead and many others were badly wounded, making this the bloodiest naval battle of the war. The Chesapeake and her crew were taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where surviving crewmen were imprisoned, including 18-year-old Ebenezer, his left leg injured. Captain Lawrence died in transit and was buried in Halifax.

The defeat was a brutal blow for the Americans. Shortly after the loss, conspiracy theories began to swirl in the media, and a naval inquest looked at the inexperience of the Chesapeake’s crew, as well as the officers’ orders to remove Captain Lawrence from the deck. Since Ebenezer’s obituary claimed that he had supported the injured Lawrence, was he also among the men who followed the order to bring the captain below deck?

Eleven months later, following a prisoner exchange, Ebenezer was shipped to Providence, RI, in July 1814. He was discharged at the Charlestown Navy Yard in August of that same year. During the same period, Captain Lawrence’s body was exhumed and re-interred in the cemetery at Trinity Church in lower Manhattan – and so begins, in my opinion, the tale of the Loud fortune.

Shortly after returning to Massachusetts, Ebenezer married his first wife, Mary Cannon. The couple moved to New York City by 1815. They also started a family there, returned to Massachusetts and had more children, and by 1830 were back in New York City and having more children – for a total of 14, among them my 3x-great-grandfather, Charles Melvin Loud.

In 1834, sadly, Mary (Cannon) Loud died at 38 years of age, leaving Ebenezer with children ranging in age from 19 to younger than 2. My 3x-great-grandfather was 7-years-old at the time.

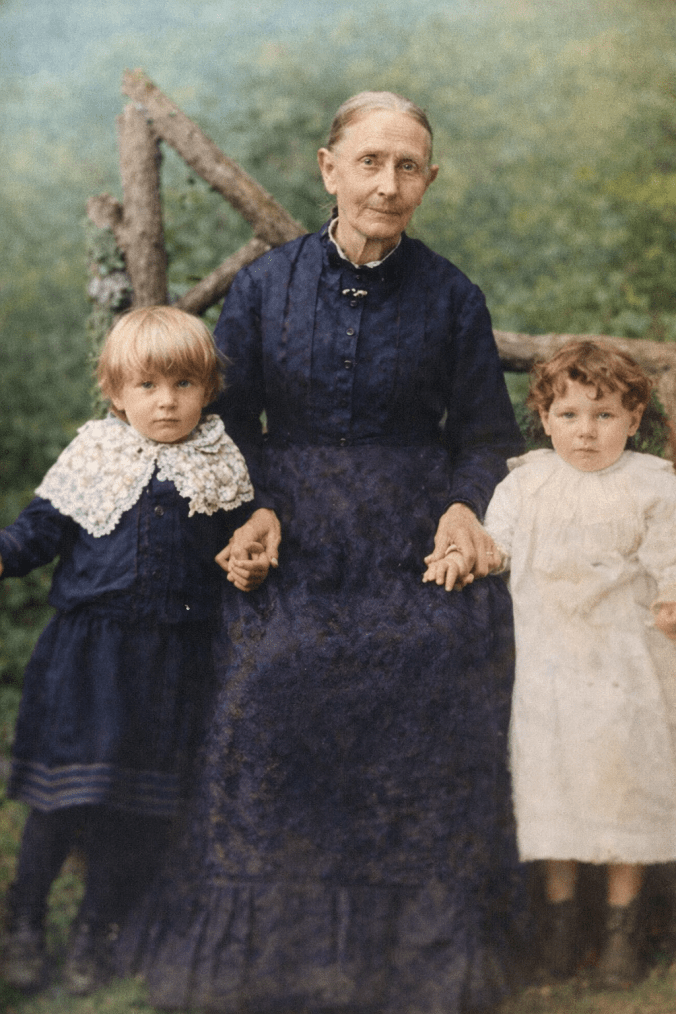

Catherine Sanford, Ebenezer Loud’s second wife. I believe the children are, most likely, grandchildren. Courtesy of 300 Years of Louds in America. Colorized by ChatGPT.

A year later, Ebenezer married Catherine Sanford, and had another 8 children, for a grand total – if you’re counting – of 22!

Working as a shoemaker, cordwainer (maker of cords), and even a police officer, Ebenezer became – in my mind – a sort of fixture on New York City Streets as he religiously made his way several times a year to Trinity Church, spending hours there, alone, contemplating, and tending to the gravesite.

Ebenezer conducted this pilgrimage for decades until about 1880, near the end of his own life, when mobility made it impossible for him. I wonder if this distressed him at all. He had made these graveside visits for more than 60 years – and I will never know the reasons why. Was it pure devotion and loyalty to his captain? Was it out of grief? Was it a remembrance of a traumatic moment in his youth? Or could he have felt responsible for the defeat, if he was in fact one of the inexperienced crew members who followed the order to bring Captain Lawrence below deck?

Whatever the answers, it’s easy to imagine how the lore of a man like Ebenezer could make its way down through the generations, part of the family’s oral history. His own son, Charles Melvin – my 3x-great-grandfather – would most certainly have heard the stories and, if he secretly followed his father and watched him through the church fencing, witnessed the solitary walks to Trinity Church, as would have his son, Charles Edward, my 2x-great-grandfather.

My great-grandfather, Samuel, born just 8 years after Ebenezer’s death, could also have heard the story of old Ebenezer, the War of 1812, and his strange obsession with Trinity Church… and then my grandfather, Harry, born in 1915…

By then, perhaps facts had become changed, like a childhood game of telephone, when a whispered phrase becomes distorted as it moves from person to person… to the point that a sailor’s respect for his captain, who was interred at a historic churchyard in lower Manhattan, morphed into a secret family fortune… a priceless trove of family stories told and shared.

Kevin, having heard the tale of the family fortune so many times, thanks for this (more believable) explanation! I love the photos of our ancestors and appreciate your research into our family history! Thank you!

Love,

Aunt Pat

Hi Aunt Pat — I’m so glad you enjoyed it! I really enjoy doing the research and being able to place these names on a tree into their time and place. Fortunately, I had C. Everett Loud help to give me a head start.