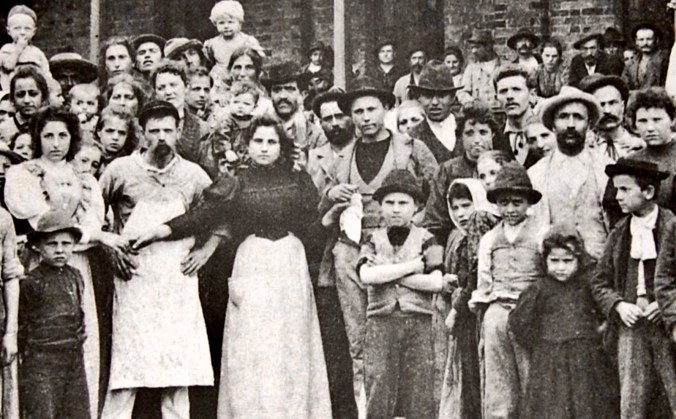

Picture it: Sicily. 1887. In the small village of Bisacquino (pictured above, courtesy of the Southern Italy Genealogical Center), a son is born to Salvatore and Maria. They name him Giuseppe and this is the start of my great-grandfather’s story, as well as my own, as I research his life and his connection to me.

That connection, by the way, seems to have stretched through time. After we returned from Sicily in April and I started playing with ChatGPT (other than some of the photos in this piece, this post is all me), I asked the program to draw me as a Sicilian peasant.

When I shared that image on Facebook, my mother called me and said the only thing she sees is the resemblance to her grandfather, Giuseppe. I then found what I think is the only photo that exists of him and placed it next to my AI-generated image. I was stunned. What do you think?

Genetically, I seem to take after my maternal side. While I see my father’s facial expressions on my own face, especially as I age, I’m also very aware of the genetic connections to my mother and her ancestry. For starters, there are thin ankles and heart disease and second toes that are longer than the big toes. If there’s a gene for having a green thumb, I have that from my mother’s side, too – specifically from my grandfather and great-grandfather.

Mom’s side of the family has been a difficult one to unravel and trace, especially because I don’t have a book like 300 Years of Louds in America to guide me. As a result, time and misspellings have often led to dead ends, wild goose chases, and even more questions.

To understand Giuseppe, it’s important to understand Sicily. For centuries, others have occupied the island – Greeks and Romans, Carthaginians and Normans, Spanish and Italians. Each culture left something – art, architecture, food, and, of course, DNA. Within this volatility, though, there was tremendous poverty – and in time, this pushed millions to seek a better life elsewhere.

Early on in my genealogical research, I found Giuseppe’s name (badly misspelled) on a passenger manifest through the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. In 1907, shortly after his discharge from the military (which I learned about through another Ancestry member), 20-year-old Giuseppe made his way from Bisacquino, Sicily, to Naples on the mainland. There, he boarded a ship to Ellis Island.

His final destination, according to the manifest, was Alabama. I assumed he made the journey from New York to Alabama by train. As you can imagine, I fell into a rabbit hole.

I wondered if Giuseppe had made this journey to America alone, a daunting adventure for a 20-year-old… or was I looking at this through today’s lens? I don’t know if he traveled with other family members or a group of friends, all looking for a better life, because I can only see the manifest page on which he’s listed.

Nevertheless, there were five other passengers on his page from Bisacquino. Surely, I thought, they all must have known each other. I reached out to the Statue of Liberty- Ellis Island Foundation to ask for assistance in deciphering handwriting and a word that looked like “fratt” or “frott.” I thought it could be some sort of shorthand for immigration purposes.

In time, I heard back from the research department… and a world opened up. According to the researchers, there was a family on my great-grandfather’s manifest page from Bisacquino: Salvatore, Giovanna, his wife, and their young daughter, Anna. Their information indicated they were traveling to stay with a relative named Pasquale C., who lived in Pratt City, AL – not “fratt” or “frott.” Giuseppe’s records also indicated his final destination was Pratt City, where he planned to stay with an uncle, Pasquale C.

The research team also added that the group most likely purchased train tickets at the railroad office on Ellis Island.

Naturally, I had to explore the subject of Sicilian immigration to Pratt City, which was founded in the 1870s and named for industrialist, Daniel Pratt, who was an investor in the area’s coal mines. By 1891, Pratt City was incorporated and was ultimately annexed by Birmingham in 1910.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a tidal wave of Sicilian immigration, with many immigrants arriving from Bisacquino. In Pratt City, they were able to find work in the coal mines, as well as in the iron and steel mills. I have no idea where Giuseppe worked.

As the new immigrants on the American block, the Sicilians faced prejudice… but they found comfort in their close-knit communities, where they could maintain their customs, like the elaborate and plentiful altars built in their homes to honor the Feast of St. Joseph on March 19.

This tradition stretched back to their homeland, where, during a drought, Sicilians prayed to their patron saint to send rain and prepared special foods to be displayed on their homemade altars. When the rain arrived, they promised to distribute the food to the less fortunate.

I then wanted to understand more of the beginnings of the prejudice experienced by Sicilian immigrants. Although I’m very aware that immigrants of all nationalities, as well as native-born peoples, have faced discrimination and violence in America, I thought it important to get a better sense of the place in which Giuseppe chose to live.

The New Orleans area, including Alabama, had a large Sicilian population. When the first wave of southern Italian immigrants arrived, the Civil War had just ended and plantation owners needed cheap labor to harvest crops, especially sugar cane. Slavery was no longer allowed, but Sicilians filled the void.

That atmosphere, which was, to some degree, tolerant, all changed in 1891. Quietly simmering under the surface was distrust of these Sicilian immigrants, with their food, culture, darker skin, brand of Catholicism, and alleged Mafia connections. On October 15, 1890, New Orleans Police Chief David Hennessy was shot in the street by a group of unknown assailants. A witness ran to him and asked him who did this. With his last breath, Hennessy whispered, “Dagoes,” a slur for Southern Italians and Sicilians.

The pot of intolerance boiled over, fueled by hateful rhetoric and allegations from media, politicians, and civic leaders. Hundreds of Sicilians were rounded up, with 19 men officially indicted in the murder of Hennessy. Nine defendants went on trial in February 1891. One month later, the verdicts were reached: six of the men were acquitted and three other hearings were declared mistrials. The nine were then returned to the local prison to face additional charges.

Needless to say, the verdicts didn’t calm the local populace. On March 14, 1891, an armed mob, thousands strong, stormed the jail. By the end of the day, 11 Sicilians were shot and/or lynched.

Because three of those killed were Italian nationals, the violence became an international incident. The American and Italian ambassadors were recalled, and the Italian government passed a resolution for a naval assault of the east coast of the United States.

President Harrison made an attempt to smooth things over, including a review of all of the legal documents, which revealed no evidence of a secret Sicilian society connected to Hennessy’s death, those arrested, nor the jury’s decision. The mafia, according to the Harrison administration, was “little more than a bogeyman to justify nativist persecution.” He also instituted Discovery Day, which we now call Columbus Day – and Italy continued with its plan to gift the US a statue of Christopher Columbus to commemorate his discovery of America. That statue now stands in Columbus Circle in New York City.

Despite all of these efforts, distrust of Sicilians and Italians continued in the country in which Giuseppe searched for a better life.

It’s difficult not to read these moments of prejudice and violence and not notice the similarities with Giuseppe’s America and today’s America. Sadly, this demonization of immigrants and of anyone seen as “other” is an all-too familiar narrative in our history.

Because it’s familiar, I have questions.

Why do we never move beyond this? When do we ever learn? When do we approach this constant immigration issue in a different way, rather than resorting to the same old tactics. If something doesn’t work, but the same solution is applied, isn’t that idiocy?

Of course, we have an uncomfortable suspicion of the answers. Perhaps the goal is to never fix the problem, allowing human beings to be used as pawns in a political battle for the Oval Office. Maybe the plan is to keep us perpetually afraid, so that abusive and discriminatory policies can be put in place in order to preserve the wealth/political/racial hierarchy.

Our leaders are wrong to do that… and we’re wrong to continually fall for it.

I’m not denying there were and are bad apples in the mix. There are… just as there are in all different fields, from law enforcement to teaching to government. But there are far greater good and decent people who are here to achieve that American Dream, to build a better life for their children and future generations…

People like Giuseppe. Although he was only 4-years-old when the New Orleans lynchings occurred, he had to have heard of it as he grew up. Letters surely arrived in Bisacquino about events and struggles in America. Relatives and neighbors must have gossiped about it – but none of that stopped him from getting on a boat to America. He chose to travel to a land in which he was despised, rather than remain in poverty among family and friends.

Not only is that a testament to his bravery and will and strength, it’s also a perfect example of the hope America instills in the world’s huddled masses yearning to breathe free. Today’s immigrants, most of whom are fleeing violence, drug cartels, and poverty, are searching for the same hope as my ancestors and yours.

It’s my belief that we have to do better, that we must be better. I’m not saying it’s an easy task, but if we are truly the greatest nation in the world, surely we should have the strength of character to roll up our sleeves and do the necessary work. If Giuseppe and millions of other immigrants risked everything to reach this land of promise and possibility, shouldn’t we live up to that standard for them, as well as for us?

As for Giuseppe, he eventually packed whatever he had and left Alabama for Independence, LA, a small agricultural community that was once called Uncle Sam. Did Giuseppe choose this place because of its patriotic name, proof of how much his new country meant to him… or was it for the promise of work on the town’s strawberry farms? Once there, did he find love?

The answer to these and other questions are a post for another day. Stay tuned.

I don’t mean to get all preachy, but sometimes I can’t help myself. These are the things that occupy my thoughts during these strange days, thoughts that keep me focused on the knowledge that 2+2=4… it does not equal 5 and it will never equal 5, no matter how many times they try to convince me.

You join me with a side of Italian heritage. Bravo! I am saddened here in Australia as we have had many protests against immigration. People don’t leave their homelands for no good reason. My family left as refugees from WWII. As I grow older, I find I’m thinking more and more about their decision to leave everything and go to the other side of the world. Such a life-changing and emotional time.

Hello Flavia… One of the reasons I’m enjoying my ancestry journey is to help me understand the past, so I can survive the present. We have also thought of leaving to live in another state or country… not so easy to do, with responsibilities, finances, etc. There’s also the fear that wherever we live can change in a vote. Then, there’s me… as tempting as it is to flee, I also want to stay and fight for my home & country. It’s a crazy world..

Sounds like very wise reasons, Kevin – the past can help us understand much – the best of luck, my friend. 😊

Pingback: Adventures in Ancestry: The Mystery of Crocifissa, Parte Uno | Nitty Gritty Dirt Man

Pingback: Adventures In Ancestry: The Mystery of Crocifissa, Parte Seconda | Nitty Gritty Dirt Man